Rob Golder - February 2022

Introduction

Kafka offers exactly-once messaging semantics, and it achieves this with its transactional API offering. However understanding what is meant by exactly-once processing is vital when deciding whether Kafka transactions are a good fit for your application and architecture.

This article explores how Kafka transactions work, what exactly-once processing means and the factors to take into consideration when deciding whether to adopt this API. A companion Spring Boot application to this article illustrates the configuration required to utilise Kafka transactions, including integration tests using the embedded Kafka broker to compare and contrast the transactional and non-transactional behaviour. The source code for this is available here. This is covered in detail in part two of the article.

The addition of transactional support to Kafka happened under the Kafka Improvement Proposal KIP-98 in version 0.11.0.0, which can be viewed here:

Exactly-Once Semantics

Typically applications using Kafka as the messaging broker will consume messages at-least-once. This is because failure scenarios and time outs naturally mean that messages are redelivered to ensure messages are not lost and are successfully processed. The upshot is that duplicate messages will need to be catered for, and a common pattern to employ for this is the Idempotent Consumer, covered in detail in this article.

There is of course overhead in message deduplication, through extra complexity, code to maintain, and possible pitfalls. Therefore the headline of exactly-once messaging with Kafka is an appealing one. It would be an ideal situation if the guarantee of exactly-once messaging meant there were no duplicate messages to be concerned with. However, digging below the headline reveals that, as might perhaps be expected, it is not quite so straightforward.

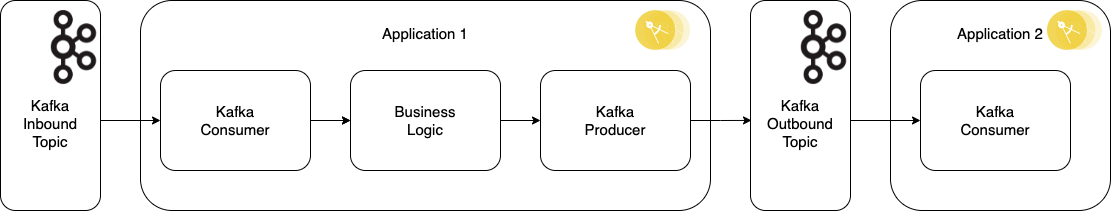

Exactly-once messaging semantics with Kafka means the combined outcome of multiple steps will happen exactly-once. A message will be consumed, processed, and resulting messages produced, exactly-once. The key here is that any downstream transaction aware Kafka consumer polling the outbound topic (as represented by the consumer in Application 2 in the diagram below) will only ever receive those resulting messages once - it is guaranteed there will not be duplicates, even if the producer has to retry sending. Failure scenarios may mean that the original message is consumed and processed (or partially processed) multiple times, but this will never result in duplicate outbound events being published.

Figure 1: Exactly-Once Delivery

Failure Scenarios

The usual failure scenarios and polling timeout during the consume-process-produce will still result in the original message being re-consumed by the application. It must do, as until the consumer offsets are updated to mark a message as consumed, Kafka does not know whether the message has been processed, is still being processed, or has failed. If messages were not redelivered in these scenarios the risk is of message loss. (For some use cases this is sufficient, dealing with at-most-once delivery, but is less common).

Kafka provides its transactional API to enable exactly-once delivery of a transactional message to downstream transaction aware consumers. When transactions are enabled the write of events being produced to outbound topics, along with the write to the consumer offsets topic (to mark a message as consumed) happen atomically within a transaction. The writes either succeed or fail as one. If a failure occurs at any point during these writes, then the transaction is not marked as completed. The transaction will either timeout and be aborted, or the message will be redelivered and processed, and the transaction is able to resume, complete, and commit (or abort).

Enabling Kafka Transactions

To enable transactions the producer must be configured to enable transactions, which requires setting the producer transactional Id on the producer factory. With this in place, Kafka can now write messages using transactions. This setting also implicitly sets the producer to be idempotent. This means that any transient errors occurring during the message produce does not result in duplicate messages being written. (The Idempotent Producer is covered in detail in this article). Finally a transaction manager must be implemented to manage the transaction.

The producing of any outbound message must be surrounded by a transaction. The following is the transactional flow:

beginTransaction is calledcommitTransaction is called to complete the transaction.When using Spring Kafka this boilerplate code is taken care of for the developer. They need only annotate the method responsible for writing the outbound events with @Transactional. Finally wire in a KafkaTransactionManager to the Spring context to make this available for managing the transaction. In the second part of this article this configuration and code is shown in an example application.

Database Transactions & REST Calls

A critical point to understand, and why this pattern is often not a good fit to meet the requirements of a messaging application, is that all other actions occurring as part of the processing can still happen multiple times, on the occasions where the original message is redelivered. If for example the application performs REST calls to other applications, or performs writes to a database, these can still happen multiple times. The guarantee is that the resulting events from the processing will only be written once, so downstream transaction aware consumers will not have to cater for duplicates being written to the topic.

One approach that might be considered to avoid the duplicate database writes during processing would be to employ Kafka transactions along with the Idempotent Consumer pattern. This pattern ties the event deduplication using a consumed messages table to any other database writes being performed atomically during processing within the same transaction. Thus these writes either succeed or fail as one. If they fail as one, the message will be redelivered and processing can be attempted again. However database transactions and Kafka transactions are separate, and in order to perform them atomically would need to be done as a distributed transaction, using a ChainedTransactionManager for example in Spring. Using distributed transactions should generally be avoided as there is a significant performance penalty, increased code complexity, and failure scenarios that could leave the two resources (the Kafka broker and the database) with an inconsistent view of the data.

Transaction Aware Consumer

In order to guarantee the exactly-once semantics a consumer must be configured with read isolation.level of READ_COMMITTED. This ensures it will not read transactional messages written to topic partitions until the message is marked as committed. (The consumer can however consume non-transactional messages that are written to the topic partition). The topic partition is effectively blocked for the consumer instance in its consumer group from performing further reads until the commit (or abort) marker is written.

By default consumers are configured with a read isolation.level of READ_UNCOMMITTED. If a transactional message was written to a topic, for such a consumer this is therefore immediately available for consumption, whether or not the transaction is subsequently committed or aborted.

If the downstream consumers are part of the same system it should be straightforward to enforce the required isolation level. However if external systems are consuming these resulting messages there is the risk that they may not have been configured to only read READ_COMMITTED messages.

Using Kafka Transactions

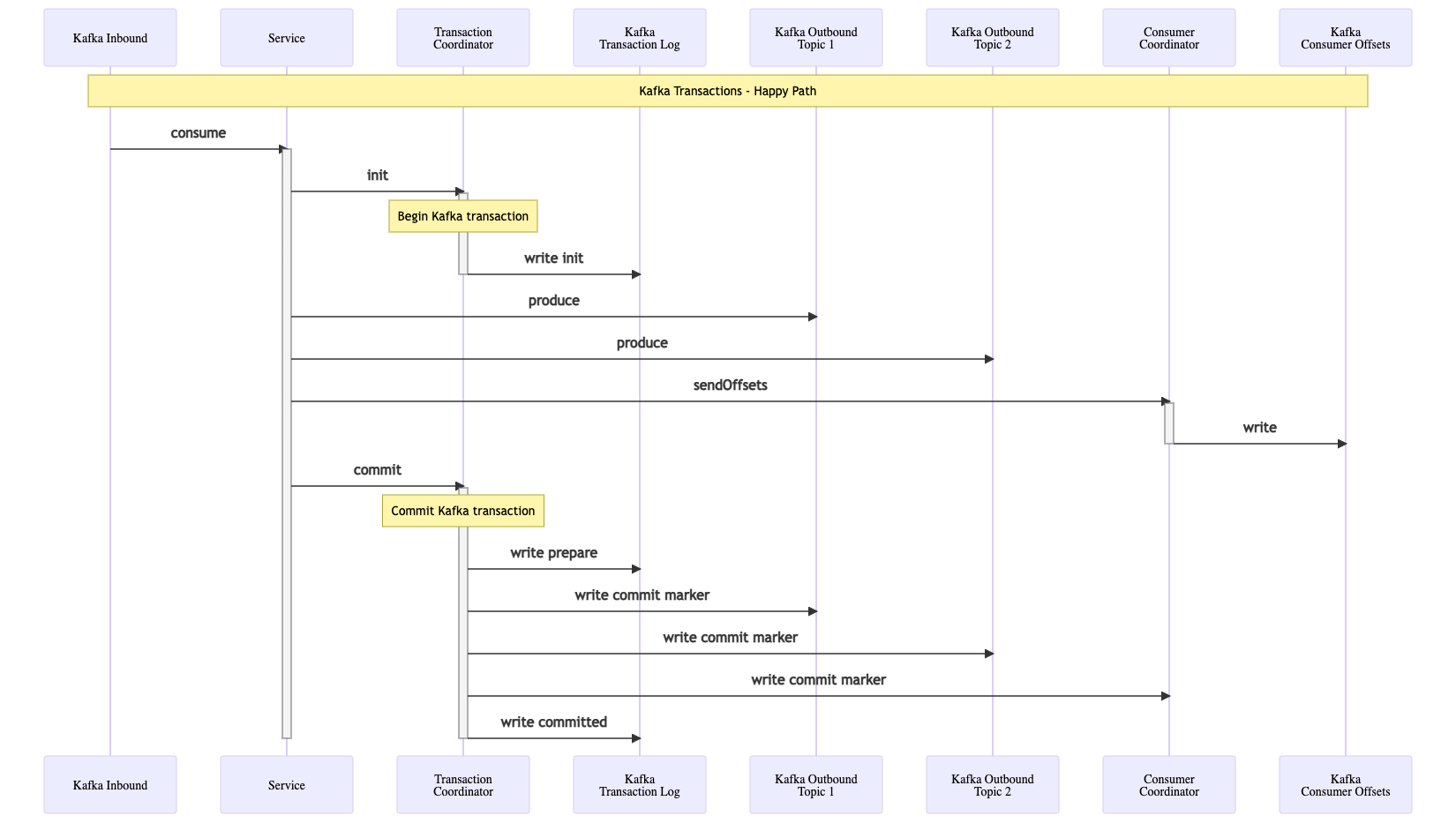

The following diagram shows the steps that take place when producing messages to a topic within a Kafka transaction. An application first consumes a message from Kafka, processes it, and then publishes outbound events to Kafka via its Producer. In this example it produces two messages to two different topics.

Figure 2: Kafka Transactions Happy Path Flow

Within the Kafka broker there are the Kafka topic partitions where the outbound messages are written, and the Transaction Coordinator. As its name implies the Transaction Coordinator is responsible for coordinating the transaction as it progresses, utilising a transaction log which the Coordinator uses to track the progress. The transaction log is an internal topic that benefits from the resilience provided by Kafka. It requires that at least three broker instances are configured to ensure that writes to the log are replicated, guaranteeing its consistency.

There is also a Consumer Coordinator component which is responsible for writing to the internal consumer offsets topic, to mark messages as consumed. These writes also need to take place within the transaction to ensure atomicity with the outbound message writes. Normally the consumer would be responsible for calling the Consumer Coordinator to perform these writes. However in order to include the write to the consumer offsets topic within the transaction then the offsets must be sent to the Consumer Coordinator directly from the Producer.

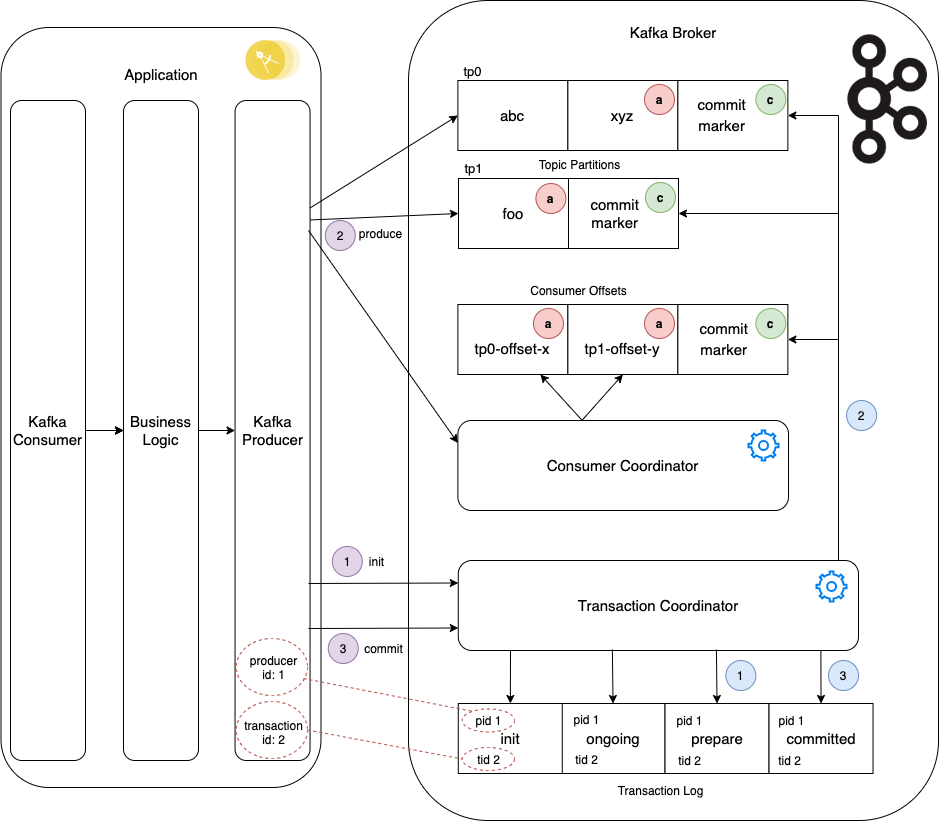

The next diagram follows the same flow as depicted in the above sequence diagram, illustrating the components in play. The application consumes a message, processes it, and produces two outbound messages: ‘xyz’ to one topic partition and ‘foo’ to a second topic partition.

Figure 3: Coordinating Kafka Transactions

Stepping through the flow, with the application having consumed and processed an inbound message and now at the point of emitting its outbound events:

The Producer calls the Transaction Coordinator to initialise the transaction, passing its producerId and transactionalId. The Transaction Coordinator writes an entry in the transactional log showing the transaction has been initialised.

The Producer calls the Transaction Coordinator to initialise the transaction, passing its producerId and transactionalId. The Transaction Coordinator writes an entry in the transactional log showing the transaction has been initialised.

The Producer writes the two events to the respective outbound topic partitions (tp0 and tp1), and calls the Consumer Coordinator with the consumer offsets which it writes to the consumer offsets topic. These writes are marked as

The Producer writes the two events to the respective outbound topic partitions (tp0 and tp1), and calls the Consumer Coordinator with the consumer offsets which it writes to the consumer offsets topic. These writes are marked as  , with two consumer offsets writes (tp0-offset-x and tp1-offset-y) correlating with the two outbound message writes.

, with two consumer offsets writes (tp0-offset-x and tp1-offset-y) correlating with the two outbound message writes.

Further calls are made between the Producer and the Transaction Coordinator tracking the transaction state as it progresses, which are reflected in the transactional log. These are not shown in detail on the diagram.

The Producer calls the Transaction Coordinator to commit the transaction.

The Producer calls the Transaction Coordinator to commit the transaction.

The Transaction Coordinator now performs the following steps:

The Coordinator marks the transaction as 'Prepare' in the transaction log to indicate that the transaction is about to be committed. At this point, whatever happens, the transaction will complete.

The Coordinator marks the transaction as 'Prepare' in the transaction log to indicate that the transaction is about to be committed. At this point, whatever happens, the transaction will complete.

The Coordinator writes a commit marker

The Coordinator writes a commit marker  to each of the two outbound message topic partitions (tp0 and tp1), along with a commit marker to the consumer offsets topic, marking all three as committed.

to each of the two outbound message topic partitions (tp0 and tp1), along with a commit marker to the consumer offsets topic, marking all three as committed.

The Coordinator marks the transaction as 'committed' in the transaction log.

The Coordinator marks the transaction as 'committed' in the transaction log.

The transaction is now successfully committed, and downstream consumers with read isolation level of READ_COMMITTED can now consume these messages.

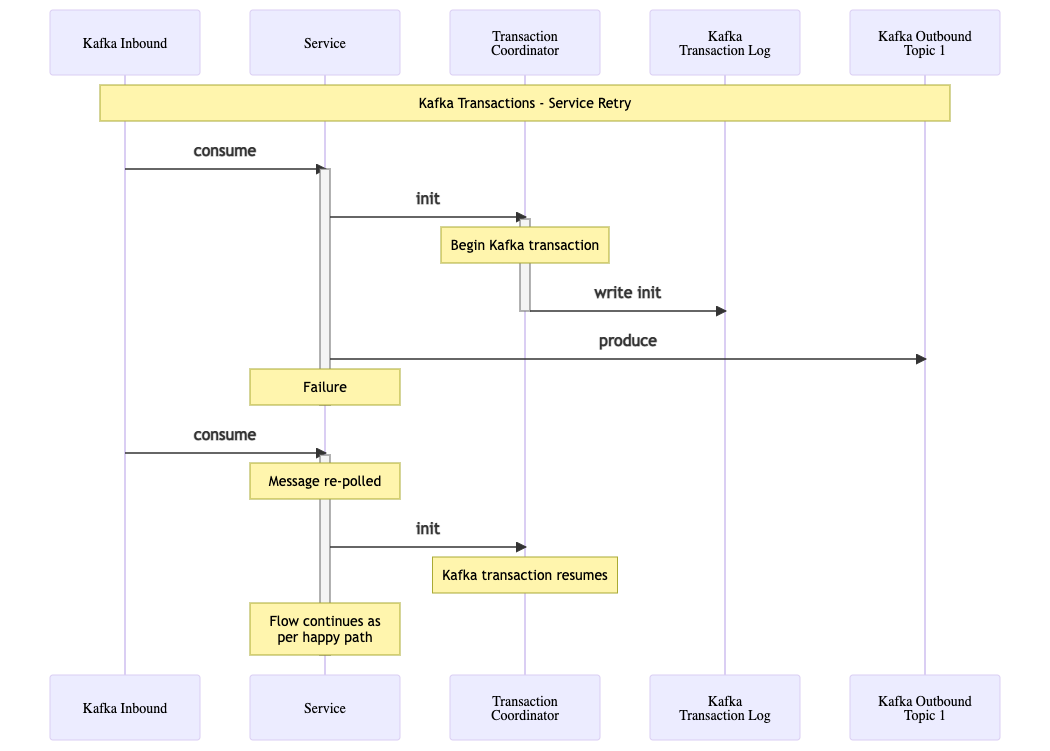

Service Retry

In the scenario where a transaction is initialised and ongoing, but the service fails, then the original message is re-consumed on the next poll. The producer again attempts to start the transaction, and the Transaction Coordinator uses the producer Id and transactional Id to locate a matching transaction and discovers that it has neither committed nor aborted. It therefore resumes the transaction, ensuring any message is only committed (or aborted) exactly-once.

Figure 4: Kafka Transactions Service Retry Flow

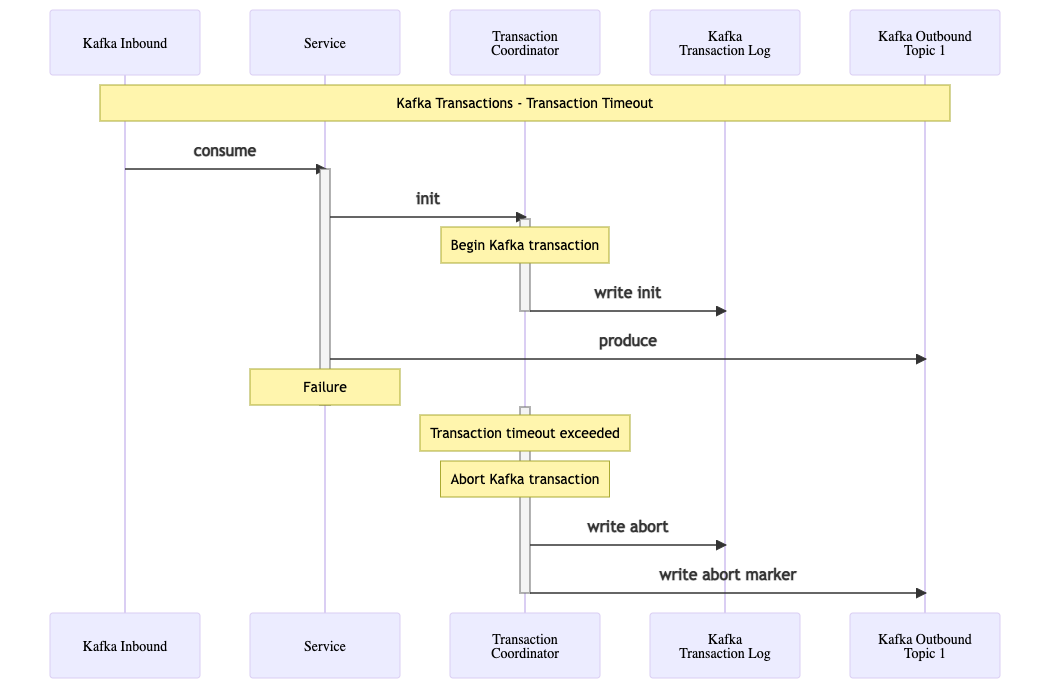

Transaction Timeout

If there is a failure in the transaction then instead of writing a 'committed' message to the transaction log it will instead mark it as 'aborted' in the transaction log, and write an 'abort marker' to the topic partition. This will happen if for example the transaction is initialised by the Producer, but does not complete within the configurable transaction.max.timeout.ms period.

Figure 5: Kafka Transactions Transaction Timeout Flow

Conclusion

Kafka Transactions provide the headline exactly-once messaging semantics, however its usage fit will depend on the requirements of the application and what else needs to be guarded against around duplicate processing. In particular the fact that these transactions are not atomic with any database transaction means great care would be needed if needing to combine the two. Failure scenarios still mean messages may be processed multiple times, so actions such as REST calls and database writes can still happen multiple times. It is also important to understand that outbound messages can still be written to the topic multiple times before being successfully committed, so the onus is on any downstream consumers to only read committed messages in order to meet the exactly-once guarantee.

Source Code

The source code for the accompanying demo application is available here:

https://github.com/lydtechconsulting/kafka-transactions

Next...

In the second part of this article the accompanying Spring Boot application is detailed, demonstrating exactly-once messaging using Kafka Transactions.

View this article on our Medium Publication.